Wait. So THAT’S what the bailouts were about?

One of the reasons that no one went to jail for the elite control fraud that caused the financial crisis is because of the pervasiveness of the criminality. You couldn’t send one guy to jail without having that guy very publicly rat out everyone else. To get to a high level on Wall Street you had to be dirty, like in a corrupt police department. No one trusts the one guy who won’t take bribes. Which brings us to Maurice “Hank” Greenberg, the former AIG CEO who is now, for lack of a better word, ratting everyone else out.

AIG, of course, is the massive insurance company which was bailed out by the government, with the Fed taking an 80% ownership stake in 2008. The AIG bailout was a strange deal, and it was renegotiated many times over the years. In a normal clean financial company resolution, AIG shareholders would have gotten wiped out. In the bailouts for Goldman, Morgan Stanley, and most of the big banks, shareholders got to keep their shares. AIG shareholders, by contrast, got to keep a little bit of what they had, a sort of split the baby in half deal. Hank Greenberg, as a shareholder, is extremely angry that he was treated this way. He thinks that he was not given equal treatment to Goldman shareholders, and in that he’s right. Most of us think that he should have been wiped out, and Goldman’s shareholders should have been wiped out too, so there’s little sympathy for this very rich man. But it’s utterly true, and everyone (even the most bank-friendly journalistAndrew Ross Sorkin) is acknowledging that it is true, that the government treated AIG shareholders differently. Greenberg is alleging, with good reason, that the motive here was quite sordid.

To understand the backstory, let’s take a quick look at AIG’s role in the housing bubble. Broadly speaking, AIG sells insurance, and one of its divisions (AIG Financial Products) sold a very specific type of insurance called a credit default swap. If you were a big bank and you owned a mortgage backed security (stuffed into a collateralized debt obligation, or CDO), you could buy a credit default swap against the possibility that the security would default. Then, because you owned this insurance, whatever that security might contain, be it good loans or the most toxic dreck imaginable, it was as good as gold. Default? No problem, AIG had you covered. The problem was that AIG covered everyone in the market (well not everyone, but a lot of the big players especially Goldman) so while the company had a really big balance sheet, it ended up being liable for sums that were larger than the amount of capital the parent company could access. There were other serious problems at AIG, such as its securities lending operation, but those aren’t as relevant to the story. And yes, technically speaking, a credit default swap wasn’t legally considered a type of insurance, it was considered a ‘derivative’. But that was just a legal fiction so that insurance regulators, who would have forced AIG to hold enough money to back its bets, couldn’t touch the company. A credit default swap is insurance.

So anyway, AIG blew up because it guaranteed an entire collapsing market of mortgage-backed securities. The Federal Reserve came in and pumped money into the company, for fear of the whole system collapsing. So why the lawsuit? Seems open and shut. Beyond that, Greenberg wasn’t even the CEO of AIG at the time of the crisis, he had already been dispatched for accounting shenanigans by then-New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in an earlier blood feud. The answer is that Greenberg plays hardball, and he’s still a big shareholder in AIG. Beyond that, he was excluded by the government from negotiations during the restructuring of a company he ran for decades, so he has a personal motive in spending his time and money harassing Geithner, Paulson, Bernanke, and company.

There have been a lot of books on the financial crisis, and most of them boiled down to a he said/she said debate over whether the bailouts were necessary, and whether they had to be done the way they were done. Bailout, Too Big to Fail, Bull by the Horns, Stress Test, Econned, On the Brink, In Fed We Trust, The Big Short, House of Cards, Reckless Endangerment, etc… Beyond that a lot of ink and pixels have been spilled to go over the minutia of the narratives, as well as government reports from many different agencies, inspector generals, and special investigators.

That said, there’s still a lot we don’t know about the saga. Sure, Bernanke, Geithner, and Paulson have told their sides of the story, through friendly reporters or through books of their own. But no one has had the chance to cross-examine them, to demand they prove that what they were telling the public was true (my read of Geithner’s book was that his recollection of the bailouts was a long and charming set of lies, but you can draw your own conclusions). But now these men are being put on the stand, and an alternative set of facts is coming to light. We’ve always had alternative theories about what happened during the pressure-filled days of the bailouts, but actual evidence has been based on self-serving portraits from CEOs, regulators, and the reporters who love them. And guesses.

No longer. We have already learned a few interesting facts about AIG (courtesy of Yves Smith). First of all, we learned that AIG didn’t necessarily need to be bailed out by the United States government. There were two and a half offers on the table to recapitalize the insurance company. One came from China, which offered to buy parts of the company. Paulson prevented this from happening. We don’t know why, though it could be due to national security concerns (rumors of AIG being heavily involved with the CIA have always floated around). The second offer came from rich Middle Eastern investors, represented by Senator Hillary Clinton (through her friend Mickey Kantor). This didn’t happen either, and again, we don’t know why. Could be national security. But the third offer suggests otherwise. The New York financial regulator offered to let AIG dip into $20 billion of capital it had in an insurance subsidiary, but Geithner said the company didn’t need it. You heard that right — Geithner turned down an internal recapitalization of AIG. $20 billion wasn’t enough to plug the hole, but it wouldn’t have hurt.

There’s more funky stuff that went on. The board of AIG was never even shown the term sheet for the bailout by the government, and the board only approved it because their lawyer — superlawyer Rodge Cohen —made a dramatic reversal of his legal position. Cohen at first told the board that a bankruptcy was a reasonable option, but a few days later he said that if the board chose bankruptcy rather than the government offer, sight unseen, the board members could be personally liable. At the same time, Cohen was alsorepresenting AIG counterparties, and was informally advising the government. Whoa there.

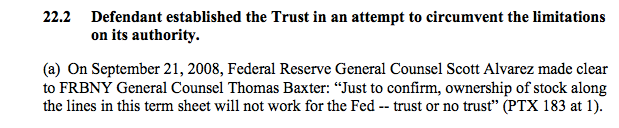

In addition to all this, we’ve learned that the Fed, in doing all of this, was probably breaking the law. First, the New York Fed changed the terms of its offer without authorization from the Board of Governors, which was a no-no. More importantly, the Federal Reserve simply could not do what it was doing, which was to buy shares in AIG and take a controlling interest (even if it stuck the shares in a trust, which was the structure it chose). Here’s Scott Alvarez, the Fed’s attorney, saying that.

This legal jeopardy also explains a lie that Bernanke told about the commercial paper market (which is the mechanism big companies use to borrow money). The week before the bailouts passed Congress, Bernanke explained to Congress that the commercial paper market was freezing up. If they didn’t approve the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), even companies like General Electric would go down. After Congress approved TARP, Bernanke then created a wholly Federal Reserve-concocted facility to back the commercial paper market, thus showing he could protect that market with or without TARP. Why did Bernanke want TARP so badly? Because the Fed needed Treasury to get the authority to buy shares, so Treasury could take the Fed’s illegally held AIG shares off their hands.

In other words, we learned that AIG was bailed out by the Federal Reserve because Paulson, Bernanke and Geithner wanted it bailed out by the Federal Reserve. They exceeded their legal authority to buy AIG for the government, and then lied about it. The $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program then bailed them out of this jam.

Greenberg alleges that their motive was to steal AIG from its shareholders, and then funnel money through AIG to banks like Goldman. There’s compelling evidence this is true; we also learned that banks, even Bank of America and Goldman, were willing to give up some of the money they were owed by AIG as part of their credit default swap payoffs. They would take less than 100 cents on the dollar for counter-party payouts. But Geithner ensured that these banks would get 100 cents on the dollar, as well as legal indemnity. To put it another way, AIG owed these banks a bunch of money, but if it had to pay the banks, it would go bust. But if it didn’t pay the banks, the banks would lose money. The banks were willing to lose a little bit of money, but Geithner said no no, you don’t have to lose any money in the deal at all. The accusation is that Geithner and co. shot AIG in the head, and then let other banks feast on its rotting carcass (liberally spiced with government money). Paulson has actually confirmed this was the goal. Big bank shareholders got bailed out, while AIG shareholders only got partially bailed out, both of course by the public. It was an utterly selective political judgment to choose one set of actors over another set of actors.

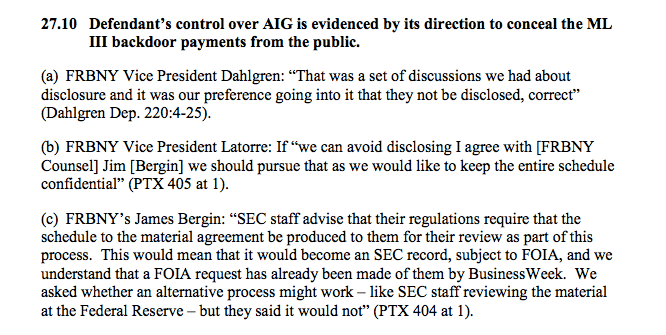

What’s really interesting is not just this allegation, but how the New York Fed — run at the time by Tim Geithner — tried to hide it. Here are several examples of New York Fed officials explicitly trying to avoid the Freedom of Information Act, as well as SEC disclosure requirements. (See page 72.)

Eventually Republican Darrell Issa, of all people, got information of who was benefitting from the AIG death rattle (Goldman, Soc Gen, etc), and leaked it. Even so, the ‘AIG as backdoor bailout’ theory was vehemently denied for years, until now. Now it’s being understood, even by people like Hank Paulson, as true. Sorkin, says as much in his piece in Dealbook.

The government never sought to couch A.I.G.’s lifeline as a way to push money into the hands of Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank, Société Générale and the dozens of other banks around the world that were the beneficiaries. That idea was never going to win a popularity contest. But that was the effect of the assistance to A.I.G. And that was the point.

Dean Baker shows the significance of this statement, and notes that the idea of AIG as a backdoor bailout “was not something generally conceded in policy circles.”

[This] matters because if everyone understood that the $192 billion injected into AIG was largely about keeping big banks from failing then there might have been more political support for breaking up the big banks and in other ways restricting their conduct. Conceding this point now that the debate over financial reform is largely in the past seems more than a bit dishonest.

In other words, Greenberg’s case is revealing that the bailouts were done selectively, and there was an attempt to cover up what happened. The Federal Reserve and the Treasury ended up treating Goldman/JP Morgan/Citigroup shareholders and employees exceptionally well, AIG shareholders less well, and the public like irrelevant peasants. Greenberg is right to complain about the unequal treatment. Of course he doesn’t deserve any money himself, because AIG really was insolvent, and he was treated better than he should have been. If the judge could dispense justice, the judge would rule in Greenberg’s favor, and then simply take away the money that big bank shareholders got to keep, claw back bank bonuses, and then also confiscate the rest of Greenberg’s assets held in AIG stock. That would be equal treatment for all citizens. Of course the judge can’t do that. The best he can do is let the trial move forward, and show the public what really happened.

There is an attempt to make this whole episode go away, to say that the government’s decisions at the time, though perhaps illegal and perhaps unfairly favoring a set of actors over another, were necessary. And besides, the bailouts made money. And none of this is news, anyway, so what are you whining about?

This narrative is fundamentally dishonest. Opponents of the bailouts said a lot of things at the time about the motives of the people in charge. It turns out that bailout opponents were largely correct, and the bailout apologists were lying and/or wrong. Increasingly, the public, judges, and politicians will recognize that the way the corrupt manner in which bailouts were done turned property rights into an explicit reflection of arbitrarily exercised political power.

Once it is broadly recognized that property rights in the post-bailout era truly are such an arbitrary exercise of political power, then a lot of things become possible. I believe in property rights; they are an important part of a just society and a mechanism to protect people from tyrannical public power (as long as they are enforced equally and with an understanding that they must also be balanced against other questions of justice, such as the threat of private monopolies to our freedoms). But because of these bailouts, no one can with a straight face claim we live in a culture that enforces property rights as a mechanism to protect individual liberties. And I’m not sure the bailout proponents are going to like where that leads.

Email me when Matt Stoller publishes or recommends stories

Enter your email

No comments:

Post a Comment